Note: This photo-essay is in the 'living' section of the 19-25 June 2015 issue of FilAm Star, the weekly 'newspaper for Filipinos in mainstream America published in San Francisco, CA. This author/blogger is the Manila-based special news/photo correspondent of the paper.

As prelude to our personal observance of the 117th anniversary

of Philippine Independence, we pored through the Propaganda exhibit at the

Lopez Museum & Library, and listened to historian Ambeth Ocampo’s discourse

on “(A)lamat at (H)istorya sa Paghahanap ng Kalinangan ng Sinaunang Filipino” during

the inaugural Lekturang Norberto L. Romualdez

of the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino (KWF) at the Court of Appeals auditorium

in Manila.

“Propaganda” immediately brings to mind patriotic

Filipino expatriates in Spain who fought for reforms in their native land

through their fortnightly newspaper La Solidaridad (Sol), which they published

in Barcelona and Madrid for almost seven years, from February 1889 to November

1895.

|

| Picture from the Biblioteca Nacional de Espana. Juan Luna painting can be seen at the Lopez Musuem & Library. |

Juan Luna expressed the vision of the reformist

ilustrados in his España y Filipinas, which he painted in 1886. The Lopez

Museum & Library has a copy of this painting that shows a woman in red classical

dress (Spain) holding a lady in white baro and blue saya (Philippines) by the

waist, and leading her toward a bright

horizon as they ascend a staircase strewn with flowers.

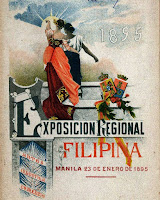

This painting was adapted by the Spanish colonial

government as the cover illustration of the catalog of the Exposicion Regional

Filipina held in Manila in 1895 to showcase the social, cultural and economic

activities in the colony. Propaganda indeed for Spain guiding her colony to a

bright future!

The revolutionary movement that came also had its own

propaganda press to spread cause for independence from Spain to the Filipino

masses. The Katipunan propagated its ideals through the writings of Andres

Bonifacio and Emilio Jacinto in the Kalayaan, their newspaper in Tagalog. Thus,

the Katipunan gained many adherents in the provinces in Southern and Central

Luzon.

After Kawit 1898, the new republic also needed propaganda

media to get the respect and recognition of foreign powers and to announce the

nation’s aspirations. Its official organ (1898-1899) published the decrees of

the government and patriotic literature. The most famous propaganda paper was

edited and privately owned by Gen. Antonio Luna: La Independencia. When the

Aguinaldo was on the run from the Americans, so was La Independencia with its

few fonts of type, and its old Franklin handpress, packed into a carabao cart.

|

Propaganda exhibit:at the Lopez

Museum &; Library:

La Independencia of 25 December 1898.

|

With the onset of peacetime in the American colony, the

Filipinos began exercising their new freedoms, particularly freedom of speech. The famous “Aves de Rapina” libel case of 1908

was brought about by attacks on the Secretary of the Interior Dean Worcester in

the nationalist paper El Renacimiento.

The publicity campaigns of the Philippine Press Bureau in

Washington greatly helped the Philippine missions for independence to the

United States from 1919 to 1924. The campaigns were intended to develop the interest

of the U.S. Congress and the American public in the Philippine issue. A privately owned monthly magazine, The

Philippine Republic (1924-1928) publicized the independence agenda and played

up achievements of Filipinos here and those in the United States to highlight

their capabilities for self-government.

|

| Picture from the Lopez Musuem & Library. |

Japanese counter-propaganda in various media vis-a-vis

Isip’s Fighting Filipino are on exhibit at the Lopez Museum. Among these are

posters hyping on the Asian co-prosperity sphere, movie posters glamorizing

Philippine-Japanese partnerships, and cartoons depicting happy relationships

between the masses and Japanese soldiers.

Up on the walls too are the editorial cartoons of

Gatbonton in the pre-martial law Manila Chronicle. These are drawn commentaries

relating usually to current events or personalities. Gat’s cartoons on our election system and

Filipino politicians remain relevant today as ever.

Woven into the Propaganda exhibit are artworks in the

museum collection done by our famous 18th century masters, national artists,

and contemporary artists.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines propaganda as

“ideas, facts, or allegations spread deliberately to further one's cause or to

damage an opposing cause; [and] also a public action having such an effect.”

No comments:

Post a Comment