In our previous post, we cited Alvaro Martinez's account that by the 1930s, the Filipino tradition of gift-giving at Christmas time had been westernized. He said that only children used to be the recipients of gifts from relatives and godparents. Perhaps, this still lingers in the Filipino consciousness when we hear about Christmas being "para sa mga bata" (for children only) even if we all scour the malls and the tiangges for presents to adults as well.

Mary Macdonald's Suggestion for Christmas Shopping in her The Philippine Home corner in the December 1929 issue of Philippine Magazine confirms that the Americans clearly influenced the transformation of Philippine Christmas into what our generation (post-WW2) became accustomed to. This includes the expensive presence of Santa Claus in the picture.

|

| This store in Escolta had mostly sports items to suggest for the gift-giving to children and adults. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

She was talking about gifts for children, mothers and fathers. We may infer that she was addressing the American community, and the Filipino readers of the magazine, which comprised the educated and well-off, the new middle class and the old rich, at that time. Thus when she said "children everywhere are talking about Christmas, and what they want Santa Claus to bring them", she could have been referring to the children of the privileged class.

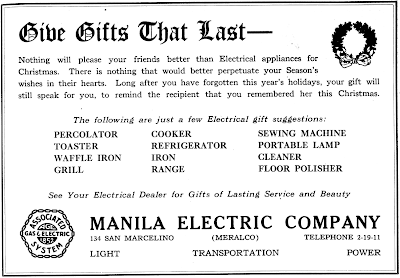

|

| Meralco suggested electrical appliances as Christmas gifts. Source: Philippine Magazine (Dec 1929). |

Let's remember that the democratized public school system started the osmosis of American culture and lifestyle into the Filipino mind. By the 1930s, Christmas was already party time for American business in the Philippines. If we look at the advertisements at that time, the target market was the affluent class. In due time, as we all see every year, the frenzy for buying (and expecting) gifts spread to all social classes.

|

| No National Book Store then but PECO where you can pick up Hemingway's 'A Farewell to Arms', a novel set during the first world war, as a Christmas gift. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

|

| Jewelry for gifts. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

Today, of course, we get a variety of goods for young kids from the local franchise of Toys R Us and the distributors of Made In China playthings.

"Books are most acceptable," she wrote. This is a timeless suggestion. Today, there is a great body of children's literature written by Filipino authors around Philippine themes.

Suggested gift items for the grown-up girls included "lovely brush and comb sets in colors to match her room, and the most fascinating organdie boudoir pillows for the dainty bed; a new dress; and a small rug for her room." Obviously, the girl in Macdonald's mind was not a provincial girl living in a nipa hut.

|

| Shoes. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

And for boy entering his teens: a book about pirates, a new Boy Scouts outfit, an inexpensive violin, or a new bicycle. Not a farmer's son, this boy.

Macdonald was not referring to our grandmother when she was looking at "beautiful pieces of pottery for the living room in colors to harmonize with the draperies ... attractive bedspreads and bolsters, or perhaps some extra pieces of silverware ." Our grandma could have been happy if she got from our grandpa "beautiful hand-embroidered Philippine handkerchiefs." But then, she could not have had everyday use for them.

Our maternal grandpa was literate and he owned horses (all butchered during the second world war), but we don't know if he subscribed to the Philippine Magazine, Graphic or Philippines Free Press. If he did, he could have loved our grandma "renewing the subscription for his favorite magazine" as a gift. He could have read El Filipino though because his best friend helped set up this short-lived news-magazine in the mid-1920s. Could he have appreciated a book on the first world war, as suggested by Macdonald? Others could have wished to receive "a new tie-clasp, and socks and handkerchiefs."

|

| Almost a century before the coming of digital cameras: A choice of cameras from Kodak and Agfa. (Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

|

| Something Filipiniana even then. Shellcraft still sells abroad today. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

|

| Christmas cards from PECO. Source: Philippine Magazine (Dec 1929). |

No comments:

Post a Comment