Note: A shorter version of this photo-essay appeared in the 24-30 July 2015 edition of FilAm Star, the weekly 'newspaper for Filipinos in mainstream America.' This author/blogger is the Manila-based special news/photo correspondent of the paper.

|

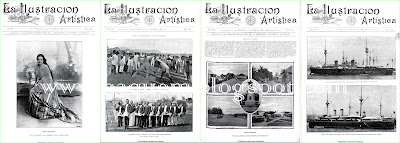

| Photographs of Felix Laureano in the front pages of these four issues of La Ilustracion Artistica: 23 Nov 1896, 07 Dec 1896, 11 Jan 1897, and 02 May 1898. (From Biblioteca Nacional de Espana) |

A selection of his photographs, vintage 1880s-1890s, on

exhibit at the Ayala Museum brings to the fore that, indeed, Panay-born Felix

Laureano was the first Filipino photographer.

After going through his works, in the La Ilustracion Artistica, a weekly

magazine published in Barcelona, Spain, in the 1896 to 1898 issues, we venture

to say that he was the first Filipino photo-journalist.

In a television interview, Canada-based historian

Francisco G. Villanueva called him the first transnational Filipino photographer

(OFW in the current political lingo) because he succeeded in professional

photography in studios he set up in Spain and in the Philippines.

Villanueva, who hails from Ilolio, started his research

on Laureano in 2010; thus, the exhibit is a showcase of his three-year research

on the photographer that he also considers an anthropologist, portraitist and landscapist.

From Villanueva’s documentation, we learn that Laureano

was born in Patnongon, Antique in 1866, the son of a wealthy businesswoman and

a Spanish friar. He and his six siblings grew up in Bugasong, where their

father was the parish priest.

|

Left photo was about an announcement to a bullfight in the Iloilo bullring (right photo),

The bullring was a bamboo strucrure. (From Biblioteca Nacional de Espana.)

|

He was 17 when he attended school at the Ateneo Municipal

de Manila in 1883. He stayed there for two years. Not much is known after Ateneo, said

Villanueva, until he opened a photo studio in Iloilo in 1886. He could have worked

as an apprentice under one of the master photographers in Manila.

Laureano was 21 when he participated with 40 photographs

at the 1887 Exposicion General de Filipinas in Madrid where he received an

Honorable Mention.

In 1892, he returned and visited Iloilo, but he went back

to Barcelona that same year. Before then, he had participated in the 1888

Universal Exposicion de Barcelona where his works received Honorable Mention.

He travelled in Europe, studied the latest photography developments in Paris,

and attended the 1889 Universal Exposicion where the Eiffel Tower was launched.

Back in Barcelona, he received citation at the Exposicion

National de Industrias Artisticas, and was singled out by the newspaper La

Vanguardia. Between December 1892 and 1901, Laureano opened three photo studios

there. Laureano could have known the

ilustrados of the Reform Movement because the La Solidaridad congratulated him

for the opening of his studio in 1893.

|

The Jaro Cathedral with a bamboo Eiffel Tower in the foreground.

(From Biblioteca Nacional de Espana)

|

His works began to be published in 1896, and until the

end of that century, his photographss appeared in La Ilustracion Artistica, La

Ilustracion Espanola y Americana, and Panorama Nacional. Two of his colored photos were published in an

1899 issue of Album Salon, the first Spanish illustrated magazine in color.

We studied around 90 of his photographs in the La

Ilustracion Artistica from November 1896 and May 1898.

Five issues of the weekly paper featured his works in the

front page covers: 23 November 1896 (a mestiza in an elegant and colorful

costume of the country); 07 December 1896 (a typical Bisayan fighting game, and

the principalia or local consultative body for administrative matters), 11

January 1897 (‘Philippine Views,’ a montage of five photographs taken around

Manila), 02 May 1898 (the battleships Pelayo and Infanta Maria Teresa of the

Spanish Navy) and 16 May 1898 (the coastguard battleship Numancia of the

Spanish Navy).

|

Cuadrilleros or rural guards.

(From Biblioteca Nacional de Espana)

|

Most of his works in Ilustracion Artistica were in the

realm of photo-essays because all the photographs were described in detail,

probably in the same manner that he did for the Recuerdos. The essays were not

by-lined but there could have been no other Filipinos in Barcelona as

knowledgeable of the Philippines, its people and customs, except Laureano. Yes,

there were the ilustrados but they were using their pens to agitate for reforms

through the La Solidaridad.

The descriptive essays on his eight pictures in the 23

November 1896 were preceded by an explanatory note, probably by the editor,

which said that with the attention of Spain focused on the ‘remote

archipelago’, it was appropriate to include in the issue ‘some pictures

depicting typical scenes and customs, convinced that our subscribers will

welcome seeing them.’ These did not have photo credits, but the editor informed

that ‘these are taken from photographs provided by Mr. Felix Laureano’. The whole composition occupies more than one

page of the weekly paper.

|

'Una Boda'- wedding party followed by a music band.

(From Biblioteca Nacional de Espana)

|

If the negotiations succeed, a wedding date is set, and

the groom’s party commits to pay for the wedding feast. A ritual is also

described about the groom walking around for scrutiny, getting accepted by the

girl, and turning over a symbolic key to the groom to signify he becomes master

of their house after marriage.

|

Datu Piang, his family and followers.

(From Biblioteca National de Espana)

|

The accompanying long descriptive essay, almost a full

page, titled ‘Types, customs and views of the Philippines’ was also preceded by

an introductory note from the editor to justify the publication of many

pictures which came ‘from the kindness of the well-known photographer of the

city, Felix D. Laureano.’ The

justification had something to do with the ‘current insurrection’ growing in ‘those

islands in the Great Asian Archipelago.’

The accompanying descriptive essay titled ‘Views of the

Philippines’ appear on top of the montage of five Laureano photographs in the

front page of the 11 January 1897 issue of the Ilustracion Artistica. This one

is short compared to the previously cited cover stories.

Towards the end of the century, Laureano and the Spanish

photographer Manuel Arias Rodriguez began sharing the pages of the newspapers

in Barcelona. “Guerra Filipinas” was the tagged of Arias photographs from the

Spanish front in the Philippine Revolution.

Laureano was in Barcelona, and he got commissions to photograph the

Spanish Navy warships anchored in the port of the city. There were scant ‘Islas Filipinas’ views after

the Spaniards lost the archipelago.

|

One of two Laureano photographs taken during the banquet for the Baler survivors.

The other showed them enjoying their dinner. (From Biblioteca Nacional de Espana.)

|

It seems that Laureano’s last press photography was his

coverage in 1899 of the banquet honoring the 32 survivors of the defense of

Baler in Tayabas.