|

Source: The Philippine Republic (1926, January). 3(1):19. Washington DC. Retrieved from http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ACC6198.1926.001 |

Friday, December 31, 2010

A New Year's eve story when it was dangerous to be a Pinoy in California

It happened on the eve of the new year 1926 in Stockton ...

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Rizal Day USA during the campaign period for Philippine independence

Today, 30th of December 2010, promptly at 7 o'clock this morning, His Excellency Benigno Simeon Cojuanco Aquino III, presided over the Rizal Day ceremonies at Luneta Park to mark the 114th death anniversary of national hero, Dr Jose Rizal. As tradition dictates, he hoisted the giant Philippine flag with the assistance of top civilian and military authorities, laid a wreath of flowers at the foot of the hero's monument, and delivered a memorial message to the Filipino people.

It's not a holiday today however. PNoy moved it earlier to last Monday, 27th December, and we doubt if the citizenry even considered giving a pause for Rizalian reflection that day before they resumed their planned activities for the extended Christmas weekend.

Except for the Luneta rites, the only other Rizal Day celebration we know of is the city fiesta of Olongapo City. It's always been called 'Rizal Day' although we doubt if there is anything commemorative of the hero's sacrificial death amidst the noise and fun in the auditorium and around the festive food tables of the city households.

Rizal Day on December 30 was an eventful day among Filipinos here and abroad before the Americans restored our independence on the 4th of July in 1946. Records show that they celebrated in grand fashion with parades, dinners and other commemorative programs.

It could be that Rizal Day morphed into the 4th of July, later replaced by the 12th of June, independence day celebrations. In the pre-World War II days (peacetime to the old generation), Filipinos had no big historical event to commemorate (did we win the war against the Spaniards? the Americans?) yet. As residents of an American territory, they celebrated the holidays of their colonizers.

It was a lingering veneration of Jose Rizal, and a vintage decree issued by Emilio Aguinaldo of the short-lived Philippine Republic on 20th December 1898 that kept Filipinos observed Rizal Day with pomp and ceremony here and abroad during the first four decades of the 1900s.

The Philippine Republic, a magazine that was set up by Americans to help in the Philippine independence campaign, left us records of 'how Rizal Day was celebrated in the United States'. From issues of 1925 to 1928, we read accounts of how Filipinos in various cities in the United States, in Japan, and even Argentina kept the memory of Jose Rizal alive.

Our survey of the Rizal Day programs during those years show the following common elements --

There was a group of Filipino scholars there who called themselves The Philippines Collegians, probably because they were from the University of the Philippines doing graduate work in Harvard U. Enrique Virata, Gregorio Zara, Juan Nakpil, and their colleagues--big names later in the Philippines--organized very formal Rizal Day programs.

Here are a few reminders of how Filipinos in America remembered national hero when they were there as pensionados or self-supporting students in the universities and colleges, World War 1 veterans who opted to stay and raise families there, adventurous Pinoys who came to work in the plantations of Hawaii and California and in the canneries in Alaska, and the first generation of Fil-Ams--US-born or innocent children yet when their parents migrated there.

Sources of pictures and information:

It's not a holiday today however. PNoy moved it earlier to last Monday, 27th December, and we doubt if the citizenry even considered giving a pause for Rizalian reflection that day before they resumed their planned activities for the extended Christmas weekend.

Except for the Luneta rites, the only other Rizal Day celebration we know of is the city fiesta of Olongapo City. It's always been called 'Rizal Day' although we doubt if there is anything commemorative of the hero's sacrificial death amidst the noise and fun in the auditorium and around the festive food tables of the city households.

Rizal Day on December 30 was an eventful day among Filipinos here and abroad before the Americans restored our independence on the 4th of July in 1946. Records show that they celebrated in grand fashion with parades, dinners and other commemorative programs.

It could be that Rizal Day morphed into the 4th of July, later replaced by the 12th of June, independence day celebrations. In the pre-World War II days (peacetime to the old generation), Filipinos had no big historical event to commemorate (did we win the war against the Spaniards? the Americans?) yet. As residents of an American territory, they celebrated the holidays of their colonizers.

It was a lingering veneration of Jose Rizal, and a vintage decree issued by Emilio Aguinaldo of the short-lived Philippine Republic on 20th December 1898 that kept Filipinos observed Rizal Day with pomp and ceremony here and abroad during the first four decades of the 1900s.

The Philippine Republic, a magazine that was set up by Americans to help in the Philippine independence campaign, left us records of 'how Rizal Day was celebrated in the United States'. From issues of 1925 to 1928, we read accounts of how Filipinos in various cities in the United States, in Japan, and even Argentina kept the memory of Jose Rizal alive.

Our survey of the Rizal Day programs during those years show the following common elements --

- Recitation of "Mi Ultimo Adios"/"My Last Farewell", sometimes with a piano accompaniment;

- Musical entertainment featuring Filipino bands, orchestras, jazz groups, string quartets;

- Musical numbers from Filipino and guest American singers and instrumentalists (pianists, violinists, guitarists, etc) rendering classical and patriotic songs and compostions;

- Orations and speeches from guest speakers (pro-Independence Americans, visiting dignitaries from the Philippines, notable members of the sponsoring Filipino association);

- Recitation of Rizaliana (biography, poems and excerpts from his other literary works);

- Formal attire--the barong has not come of age yet;

- Singing of two national anthems: Star Spangled Banner and the Philippine National Anthem.

There was a group of Filipino scholars there who called themselves The Philippines Collegians, probably because they were from the University of the Philippines doing graduate work in Harvard U. Enrique Virata, Gregorio Zara, Juan Nakpil, and their colleagues--big names later in the Philippines--organized very formal Rizal Day programs.

Here are a few reminders of how Filipinos in America remembered national hero when they were there as pensionados or self-supporting students in the universities and colleges, World War 1 veterans who opted to stay and raise families there, adventurous Pinoys who came to work in the plantations of Hawaii and California and in the canneries in Alaska, and the first generation of Fil-Ams--US-born or innocent children yet when their parents migrated there.

- Brooklyn, New York City, 1924.

|

| The Filipino masons of "Gran Oriente Filipino" led the annual Rizal Day celebrations in Brooklyn, New York City. In this 1924 event, violin prodigy Ernesto Vallejo was 14 years old. |

- Boston, Massachussetts, 1924.

|

| In the Boston area, the Filipino World War 1 veterans were the leaders in the celebration of Rizal Day. |

- Los Angeles, California, 1924.

|

| The Filipino Association of Southern California called this a Rizal Day meeting, and from the program, it looked like it was a music concert. |

- Washington DC, 1925.

|

| In this Washington DC Rizal Day, Mrs Claro M Recto, soprano, a music student in Washington at that time rendered a vocal solo. |

- Detroit, Michigan, 1925.

- San Diego, California, 1925.

|

| This program tells us that the Filipinos in the United States Navy at that time were not only cooks and stewards but also musicians. |

- Salinas, California, 1925.

|

| This 1925 Rizal event was a three-day celebration. Other cities also had Rizal Day Queens. |

- Seattle, Washington, 1925.

- Crane College, Chicago, Illinois, 1926.

Sources of pictures and information:

- The Philippine Republic ( 1925-1927 issues). Retrieved from the University of Michigan Digital Library Collection, The United States and its Territories, 1870-1925: Age of Imperialism at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/philamer/

Friday, December 17, 2010

Westernization/Americanization of Philippine Christmas Gift-Giving

In our previous post, we cited Alvaro Martinez's account that by the 1930s, the Filipino tradition of gift-giving at Christmas time had been westernized. He said that only children used to be the recipients of gifts from relatives and godparents. Perhaps, this still lingers in the Filipino consciousness when we hear about Christmas being "para sa mga bata" (for children only) even if we all scour the malls and the tiangges for presents to adults as well.

Mary Macdonald's Suggestion for Christmas Shopping in her The Philippine Home corner in the December 1929 issue of Philippine Magazine confirms that the Americans clearly influenced the transformation of Philippine Christmas into what our generation (post-WW2) became accustomed to. This includes the expensive presence of Santa Claus in the picture.

|

| This store in Escolta had mostly sports items to suggest for the gift-giving to children and adults. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

She was talking about gifts for children, mothers and fathers. We may infer that she was addressing the American community, and the Filipino readers of the magazine, which comprised the educated and well-off, the new middle class and the old rich, at that time. Thus when she said "children everywhere are talking about Christmas, and what they want Santa Claus to bring them", she could have been referring to the children of the privileged class.

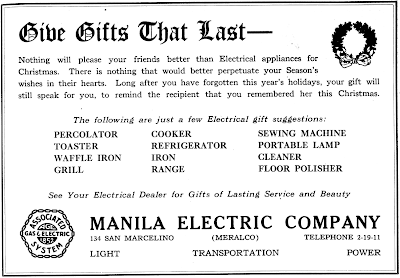

|

| Meralco suggested electrical appliances as Christmas gifts. Source: Philippine Magazine (Dec 1929). |

Let's remember that the democratized public school system started the osmosis of American culture and lifestyle into the Filipino mind. By the 1930s, Christmas was already party time for American business in the Philippines. If we look at the advertisements at that time, the target market was the affluent class. In due time, as we all see every year, the frenzy for buying (and expecting) gifts spread to all social classes.

|

| No National Book Store then but PECO where you can pick up Hemingway's 'A Farewell to Arms', a novel set during the first world war, as a Christmas gift. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

|

| Jewelry for gifts. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

Today, of course, we get a variety of goods for young kids from the local franchise of Toys R Us and the distributors of Made In China playthings.

"Books are most acceptable," she wrote. This is a timeless suggestion. Today, there is a great body of children's literature written by Filipino authors around Philippine themes.

Suggested gift items for the grown-up girls included "lovely brush and comb sets in colors to match her room, and the most fascinating organdie boudoir pillows for the dainty bed; a new dress; and a small rug for her room." Obviously, the girl in Macdonald's mind was not a provincial girl living in a nipa hut.

|

| Shoes. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

And for boy entering his teens: a book about pirates, a new Boy Scouts outfit, an inexpensive violin, or a new bicycle. Not a farmer's son, this boy.

Macdonald was not referring to our grandmother when she was looking at "beautiful pieces of pottery for the living room in colors to harmonize with the draperies ... attractive bedspreads and bolsters, or perhaps some extra pieces of silverware ." Our grandma could have been happy if she got from our grandpa "beautiful hand-embroidered Philippine handkerchiefs." But then, she could not have had everyday use for them.

Our maternal grandpa was literate and he owned horses (all butchered during the second world war), but we don't know if he subscribed to the Philippine Magazine, Graphic or Philippines Free Press. If he did, he could have loved our grandma "renewing the subscription for his favorite magazine" as a gift. He could have read El Filipino though because his best friend helped set up this short-lived news-magazine in the mid-1920s. Could he have appreciated a book on the first world war, as suggested by Macdonald? Others could have wished to receive "a new tie-clasp, and socks and handkerchiefs."

|

| Almost a century before the coming of digital cameras: A choice of cameras from Kodak and Agfa. (Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

|

| Something Filipiniana even then. Shellcraft still sells abroad today. Source: Philippine Magazine (Nov 1929). |

|

| Christmas cards from PECO. Source: Philippine Magazine (Dec 1929). |

Labels:

Christmas,

Mary Macdonald,

Meralco,

Phil Education Company

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Today's Update of Philippine Christmas circa 1930s

|

| Illustration by Pablo Amorsolo of Alvaro Martinez's Reminiscences of Philippine Christmas in the December 1930 issue of the Philippine Magazine |

In December 1930, Alvaro Martinez was already lamenting that "many beautiful practices connected with the observance of Christmas in the Philippines are slowly passing away."

After eighty years, these practices may only be alive in the ganito kami noon (this is what we were) stories of surviving great-grandparents of today's generation, or they have morphed into variants shaped by the dictates of Christmas commerce and the influences of foreign, specifically American, culture such as the Santa Claus hype.

Martinez, 1930: "The Philippine aguinaldo differs or differed from the Western Christmas gift in that it is given only to younger children, and usually not by the parents but by other relatives and friends. Godmothers and godfathers were especially called upon to bestow upon their godsons or goddaughters substantial aguinaldos at Christmas. These took the form of money, eatables, or toys. It was the common practice on Christmas Eve to change paper bills into small coins for distribution to the children who were sure to call the next day. Paper bags filled with fruits, nuts, and candies were prepared for the older children who accompanied their younger brothers and sisters. They were supposed to be too old to receive their aguinaldos in money."

Our aside: In the days before the second world war, as borne by church records, a baby girl has only a ninang (godmother) and a baby boy a ninong (godfather) during his baptism. It was rare to have both a ninong and ninang. In one case we found in the baptismal book of the early 1890s in San Narciso, Zambales, the son of a cabeza de barangay was baptized with the gobernadorcillo and his wife as godparents.

Update 2010: 'Aguinaldo' is archaic; it's now 'Christmas gift' or 'regalo' for all--members of the family, relatives, friends, officemates, service providers (househelp, messengers, garbage collectors, village security guards, et cetera).

Thus, gift buying is stressful in many ways (Christmas is a stressed season, an American newspaper said so in a front page last week) but 'tis good for the business in malls or tiangges thickly crowded with shoppers till the midnight.

We think that having multiple godparents (baptisms and weddings) a.k.a sponsors is a post-World War 2 phenomenon, and this could be just circa 1970s. We can't help being co-sponsor every now and then with new faces, may be a barangay kagawad or a senator, or a popular movie or entertainment personality.

We hate to be in the Cubao area in the late afternoon of December 25 because we don't like to see the sight of tired mothers saddled with plastic bags of gifts tongue-lashing and dragging disconsolate children to the jeepney stop for the ride home. We saw them in the morning, all their faces etched with thrill and excitement, waiting for the rides to bring them to their kids' ninongs and ninangs around the metropolis. At the end of Christmas day, was it worth traveling to and fro just so the kids' would get a gift from their multiple sponsors?

Martinez, 1930: "The money collected by the children in aguinaldos was either placed in coconut alcancias to become a part of the children's savings or was spent for clothing and other necessities. In the case of some poor families, the money was sometimes used to help meet the family expenses."

Update 2010: There may be modern variants of the coconut 'bank'. For the rich kids, the cash gifts may go for the latest electronic gadgets. Yes, it's still true, some poor kids become bread winners as soon as the -ber months set in. In shopping areas or public transport routes, there would be street children singing a carol and expecting a dole-out.

Martinez, 1930: "For the children, much of the thrill of Christmas has gone with the passing away of the custom so prevalent in former years of preparing a special new suit or dress for the day. Mothers saved for months to buy their children new clothes, no matter how poor in quality they might be. The buying of shoes was kept off as long as possible in order that the children might all have a new pair at Christmas. Christmas then stood out from the rest of the year.

"Children stayed up late on Christmas Eve making their preparations for the next day. Their new clothing was placed on chairs, neatly folded and ready for the next morning, and the new shoes taken out of their boxes and put beneath them together with the new socks or stockings. The route to be taken in visiting relatives and friends was also discussed and the customary Christmas greeting of Magandang Pasko Po was practiced.

"Nowadays good clothing is used for every day wear, so there is nothing for special occasions."

Our aside: When we were growing up, this was true for provincial kids like us. We remember only two occasions when we get to wear brand new shoes--Christmas and graduation day. Leather shoes were not often worn to school because wooden shoes or Japanese sandals would do.

Our mother and her close friends would take a day off from house chores and go to a bazaar in Olongapo for a bit of shopping for the children's and husband's clothes. She'd come home with a white polo shirt for me; it was always white. She was a seamstress; hence, my sisters would have newly sewn dresses (sometimes done just before getting dressed up for the midnight mass.)

Update 2010: Shopping, shopping, shopping for expensive signature stuff using saved allowances, advance cash gifts from parents/godparents/siblings and/or remittances of OFWs in the family; or for pseudo-signatures in the pirate market.

Thank God, some modern-day godchildren still pay respect to their godparents by doing the mano ritual (they take your hand and have it touch their forehead briefly), and they need not say 'Magandang Pasko Po.'

The linggo on the streets is different: Meri Krismas! Kahit barya lang, kuya. (Some money, big brother!. Barya in the old days was a few centavos; today, barya may mean a one, five or ten peso coin).

Martinez, 1930: "As the children and their elders dressed up for Christmas, so were the houses furbished. A general cleaning began several days before Christmas. The busy housewife used her retazos (remnants) that had accumulated to make new curtains for the doors and windows. The bamboo floor was scrubbed with lihia (wood ashes), then polished by means of banana leaves and coconut husks. The husband and elder sons busied themselves in the making of lanterns which were hung in the windows and kept lighted from the first night of the simbang gabi or early morning mass to the new year. Every house was hung with lanterns, giving the street a really festival air. These lanterns, shaped like stars, flowers, fishes, airplanes, or boats, and others with moving figures revolving within them, were much more interesting than the electric lights used nowadays."

Update 2010: We learn from here that Christmas season was purely a December affair. The lanterns were hang and lit only from December 16 to January 1!

Eighty years ago, their lanterns have taken various designs already. Through the years there could have been fads from which lantern designs were derived. The novelties we find these recent times have something to do with using recyclable materials in keeping with international advocacies to keep planet Earth green.

|

| UP Centennial Lantern Parade, Dec. 2008. Lanterns look like colorful jellyfishes. |

Of course, the lantern has also become the highlight of their own parades. The Lantern parade of the University of the Philippines has become a traditional event before the students go home for their Christmas holiday. It's been transported to San Francisco where the Filipinos at the South of Market area have been holding a Parol Festival for the last eight years.

|

| Flyer for the 8th San Francisco Parol Lantern Festival & Parade. |

Another thing to note: there's no mention of decorating Christmas trees. There were no Christmas trees in Filipino homes before the second world war?

|

| Giant Christmas tree at the Araneta Center. |

Update 2010: Brass bands have been missed for a long time. We don't remember our town band whether they made the rounds before or after the morning mass. But if there are bands going around, there would always be children tailing them and having fun.

Martinez, 1930: "The simbang gabi has lost much of its glamour. Attendance has dwindled a great deal in the past few years. People seem to prefer to stay in their beds these nights."

Update 2010: Probably, this was a sweeping generalization. Simbang gabi remains a big-attendance event.

The hours have changed though. Before the martial law years, morning mass was really early at 4am. It was moved later during the curfew years.

We've seen how the simbang gabi has changed time schedules as well from midnight to 9 o'clock last year. We think this is just right; economics and nutritional requirements dictate just one late dinner on Christmas eve.

Martinez, 1930: The bibingkahans at the street corners and on empty lots provided places where the people coming home from church could stop to satisfy the cravings of their stomachs. Long rows of crude tables and wooden benches stood under canopies of cloth or leaves. The bibingkas (rice cakes) were served with hot tea. This custom, too, is losing popularity, perhaps due to the more modem restaurants and refreshment parlors.

|

| Bibingkahan in a commercial center using traditional cooking technology. |

Update 2010: We've seen the resurgence of bibingkahans everywhere using both traditional and modern baking techniques. We've seen also variants of the original bibingka mix--new flavors and some add-ons. In MetroManila, we're still confused where to go buy the special ube bibingka; is it Bibingkinitan or Bibingkahon?

Of course, there are a lot of baked choices these days like quick-melt ensaymadas, mamons, cakes and dough-nuts.

Martinez, 1930: Church goers lingered around after attending church, and many stayed up all night, the streets and plazas and the beaches and other open places were filled with people. There was always much talk and fun. Nowadays people hurry to their homes after the mass.

Update 2010: After the early morning mass, people hurry home or to their places of work. Excursions to beaches and other tourist places are planned sometime during the holiday season.

Martinez, 1930: The lechon, or roasted pig, was as much a part of the Christmas celebration in the Philippines as the turkey is of Thanksgiving Day in America. It was a beautiful as well as common sight to see a slowly browning pig turning on a long bamboo pole above live coals. Later the roasted pigs could be seen carried by two men on the same pole on which it was roasted to some lucky family's table. Choice parts were presented to neighbors and friends. Poorer people bought parts of a roasted pig in local restaurants commonly called carihans.

Alas, the lech6n, too, is slowly losing ground. People no longer take the trouble to prepare something special for Christmas. It is easier to go to a panciteria, and, in the courses offered there, roast pig no longer occupies the place of honor.

Update 2010: Nope, lechon is still the desired centerpiece during the family reunions on Christmas day.

For midnight dinners though, it's hamon. That's the reason why this popular hamon shop in Quiapo or Binondo does not sleep at all when the season starts. There's a great demand for it. Good enough substitute for gift-giving are the boxed hams in the groceries.

There's no lack for meats for Christmas celebrations: roasted chicken or liempo from Andok's or other similar stalls for those who have to bring home the family meal.

For those with a slim budget for a family dinner, there's always a choice among the popular fast food centers--Jollibee, McDo, Chowking, and lately, Mang Inasal, where you eat all the rice you can--and the pizza huts, if a family size pie would be sufficient to brighten up the spirit of Christmas.

Martinez, 1930: "What next shall we lose?"

Update 2010: "What is lost, and must be recovered?" Simple: the meaning of Christmas. Did the child born in a manger 2,010 years ago morphed into Santa Claus?

Reference:

Martinez, Alvaro. (1930, December). Reminiscences on Philippine Christmas . Philippine magazine. 27:7(417, 484-85). Manila: Philippine Education Co. Retrieved from http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acd5869.0027.001

Martinez, Alvaro. (1930, December). Reminiscences on Philippine Christmas . Philippine magazine. 27:7(417, 484-85). Manila: Philippine Education Co. Retrieved from http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acd5869.0027.001

Monday, December 13, 2010

First Pinoys in Foreign Wars: The Filipino World War 1 Veterans

|

| There were 50 veterans belonging to the 49th Infantry Filipino Company (see their banner) during an event in Washington DC, which could have been the Veterans Memorial Day of November 1924. |

"NO greater proof can be found of the success of America's policy in the Philippines than the loyalty and friendship the Filipino people have shown her during the great war [World War 1]," wrote Maximo Kalaw in his book advocating Self-Government in the Philippines (1919), with "all the men and resources of the Islands ... offered to the service of the United States"--

"Immediately upon the declaration of war the Philippines offered to America the services of twenty-five thousand soldiers of the Philippine Militia [this was in April 1917], to be called the National Guard. Senate President Quezon, in a special trip to the United States, urged in person the acceptance of the offer as a sign of Philippine loyalty. In expectation of the acceptance of the offer, a quota of the 25,000 men was assigned to each province, and, without resorting to draft, 28,000 men soon were enrolled ready to go into training. Hundreds of our choice young men--the flower of our youth-- left their high governmental and professional positions to join America's colors ...

"Six thousand Filipinos voluntarily enlisted in the American Navy ... Four thousand Filipino laborers in Hawaii, who could have claimed exemption from the draft under the citizenship clause of the draft law, insisted on being enrolled under the Stars and Stripes. The loyalty was sincere and spontaneous on the part of the people."

When the Philippine Legislature convened in 1917, it immediately passed a resolution of commitment to America for the cause of democracy, and even allocated P4-million to build a destroyer and a submarine for the the US. In fact, a destroyer named after the national hero Jose Rizal was launched on September 23, 1918. We do not know if the destroyer was accepted by the US and deployed to Europe to help in the war efforts.

The Filipinos in the United States like the contract workers or sakadas in the Hawaiian plantations and other industries were either drafted by the US military on June 5, 1917, June 5, 1918 and September 12, 1918, or they volunteered their services.

Kalaw himself volunteered to serve, and their division "could probably have had a chance of reaching France, of joining Pershing's Army, of helping sanctify St. Mihiel and Chatteau Thierry had it not been for inexcusable delay in its organization." The delays? The US President could only call the Philippine National Guard to federal service after the enabling law was passed on January 3, 1918; the Officers' school was organized late in July 1918, and at that time, the National Guard training camp had already been named Camp Claudio in honor of Tomas Claudio, the first Filipino to die in the war in Europe.

Kalaw's division completed mobilization on November 11, which was also the day the armistice was signed. Thus, the National Guard was not able to leave the Philippines at all.

I.Q. Reyes, Filipino veteran of that war, reminisced six years later in his They Served Uncle Sam in his Foreign War (The Philippine Republic, July 1925): "We left homes, parents, sisters, brothers and loved ones to join the army, navy or the marine corps of the United States to help to fight her battles and win the war. ... We fought with American comrades side by side on land and sea. Each and every one of us, although Filipinos and of a different race, were perfectly willing to give our lives for the country that has done so much for our homeland."

Kalaw and Reyes could very well have been speaking for other generations of Filipinos to come, Philippine- and US-born, who would serve with the United States armed forces during World War 2, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and in the continuing conflicts in the Middle East.

During the war years, according to Kalaw, the Filipino people maintained their peace and restrained all agitation for Philippine independence. "All their work was one of patient cooperation, apparently forgetting for the time being their own cause. ... there was not an attempt made to remind America of the Philippine problem."

When the war ended, the Philippine Legislature even expressed through a resolution "the gratitude of the Filipino people to the United States for the part they were allowed to take in the most far reaching enterprise ever undertaken by Democracy."

The World War 1 veterans either went back to the Philippines or settled in the United States to raise families. There were those who re-enlisted in the Army, joined the Navy or the Merchant Marines.

|

| Officers and members of the Massachusetts World War Filipino Veterans' Association, Inc., 1926. |

The veterans in the US formed their associations in their cities of residence, and were also members of two posts of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) organized exclusively for Filipino veterans at that time.

One of them was Post No. 1063 with headquarters at 1521 West Colombia Avenue., Philadelphia, PA, which was organized on 05 August 1923 for "fraternal, patriotic, historical and educational" purposes including the promotion of friendship between Filipinos and Americans . In 1925, I.Q. Reyes was commander of this post.

|

| Officers and Members of Pvt. Tomas Claudio Post 1063, 1925. |

Post No. 1063 was named Pvt. Tomas Claudio Post in honor of the war hero from Morong, Rizal in the Philippines.

Claudio was 19 when he journeyed to Hawaii in 1911. There he joined other young and adventurous Filipinos working in the plantations. He'd move to California, and to the canneries in Alaska. He'd settle in Sparks, Nevada and pursue a commerce course in Clark Healds Business school, graduating in 1916.

Claudio was a clerk at the city post office when the US joined the war in 1917. He had always been attracted to the military even way back in the Philippines, and with America in the war, he applied in the US army. He was denied twice but was finally enlisted in the 41st Division on 02 November that year. On December 15, the division left for Europe, and Claudio's final destination was France.

He was first assigned in the trenches of the Toul Sector, then with the reserve division near Paris, and later at the Montdidier front. On 28 May 1918, he took part in the Battle of Cantigny against the Germans where he was severely wounded. He was not able to recover, and he passed away on 29 June in Chateau Thierry.. The United States, France and his country, the Philippines, honored his heroism.

Today, the Pvt. Tomas Claudio Post 1063 is one of 35 VFA posts based in Philadelphia. It is no longer exclusively Filipino in its membership.

In its earlyyears, the post actively participated in the city activities like " parades, memorial services and social gatherings undertaken by the Veterans of Foreign Wars, sending delegates to the National Convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars to represent it each year." It was"widely known in the city, and well supported and cooperated with by all the posts and Department and National Headquarters" being "one of the very active posts in the city"; it organized "a Ladies’ Auxiliary to participate in [their] activities, and to look after a comrade or a family of a comrade in distress" (Reyes, 1925).

|

| Rizal Day 1924 hosted by the Massachusetts Filipino World War 1 Veterans' Association. |

The Filipino veterans in key cities in the US were very active in the celebration of Rizal Day on 30 December in the years before some of them fought again during World War 2. In Massachusetts, the veterans' association hosted the Rizal Day events of 1924 and 1925 , as can be seen in the pictures here. They could have continued doing so during those years all the Filipinos in America were all campaigning for Philippine independence with the national hero as their strong inspiration.

|

| Rizal Day 1925 hosted by the Massachusetts Filipino World War 1 Veterans' Association. |

The last Filipino World War 1 veteran might have passed away many years ago. There are continuing efforts to remember who they were and their heroism in that distant war.

We've clipped the photos above with their captions of names for those who have been looking for records of their relatives in that war. Our interest was captured by veterans cited to be from Zambales particularly those from San Narciso. This led us to the Filipinos First WW1 US Military Homepage where we got the following roster of veterans from Zambales:

- Labrador Arce born 12/1/1893 Zambales; died 5/21/1963; buried Los Angeles National Cemetery; Pvt Co E 1st Hawaiian Inf inducted 9/12/1918-7/10/1919; resident of Liliha & Kukui Sts Honolulu Hawaii

- Fausto Baneros born 8/13/1884 Cabangan Zambales; Pvt Co L 1st & 2nd Inf inducted7/11/1918-7/9/1919; resident of Pahoa Hawaii

- Juan Delara born 1892 Olongapo Zambales; Sgt Co B 1st Hawaiian Inf; 9/10/1916-7/12/1919; resident of Honolulu Hawaii

- Epefanio Dial born 4/25/1896 Zambales; died 12/20/1970 Pfc Co E Hawaiian Inf; inducted 7/1/1918-7/10/1919; resident of Kahului Maui Hawaii; SS# issued Hawaii

- Alejo Diquia born 1893 Zambales; Pfc Co L 1st & 2nd Hawaiian Inf; ¾/1918-7/11/1919 resident of Camp 4 Makaweli Kauai Hawaii

- Fulgencio Esiberi born 1/20/1891 San Felipe Zambales; Pvt Co I 2nd Hawaiian Inf; inducted7/8/1918-2/1/1919; resident of Waiakea Mill Hilo Hawaii

- Pascual Garcia born 5/14/1890 Castillejos Zambales; Co E 2nd Hawaiian Inf; inducted 7/10/1918-1/31/1919; resident of Puunene Maui Hawaii

- Primitivo Gregorio born 1895 Zambales; Pvt Co L Det; Co I 1st & 2nd Hawaiian Inf; inducted 7/29/1918-1/27/1919; resident of Waimea Kauai Hawaii

- Domingo Larutin born12/3/1898 San Narciso Zambales; died 6/3/1969; buried National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific; Pvt Co I 4th; Co L 1st & Hq Co 1st 2ndHawaiian Inf; 5/13/19177/14/1919; resident of Makaweli Hawaii

- Ciriaco Mararac born 8/17/1892 Iba Zambales; died 10/20/1971 Norco Riverside California; Pvt Co G 1st Hawaiian Inf; inducted 7/17/1918-7/17/1919; resident of Kukui near Liliha St Honolulu Hawaii; laborer Hawaiian Fertilizer Co Honolulu

- Maximo Mendoza born 1896 San Narciso Philippines; Pfc Co H 2nd & Co K 1st Hawaiian Inf; 11/26/1916-7/12/1919; resident of Haiku Maui Hawaii

- Emigdio Milanio born 8/2/1898 Zambales died 9/19/1959; buried Maui Veterans Cemetery; Cpl Co E 2nd Hawaiian Inf; 5/28/1918-1/31/1919; resident of Lahaina Hawaii

- Pablo Oyando born 2/23/1890 Zambales; Pvt Co H 2nd Hawaiian Inf; inducted 7/9/1918-1/31/1919; resident of Koloa Hawaii

- Nicholo Pluma born 1891 Zambales; Pvt Co M 1st Hawaiian Inf; inducted 7/29/1918-7/12/1919; resident of Kukuihaele Hawaii

- Lorenzo A. Ramos born 1889 Iba Zambales; Cpl Co M 1st Regt Hawaiian Inf; 7/10/1916-7/10/1919; resident of Honolulu Hawaii

Our 'Bravo!' to Maria Elizabeth Ambry of California for setting up the Filipinos World War 1 US Military Services Homepage .

From her we borrow an appropriate coda for this article:

"Filipino veterans after WW1 war. Many veterans went to the Philippines, Hawaii, California, Washington, Alaska, Oregon, New York and other places to raise families. Other veterans joined the Navy and the Merchant Marines or re-enlisted in the Army, serving once again in WW11 and Korean War, because their "war that will end other wars" failed to deliver the promise of peace. Some veterans who suffered military service connected disabilities (SCD) were entitled to vocational training and $100.00 monthly pension, but the 1933 creation of the Department of Veterans Affairs, stripped these benefits and the 1945 G.I. Bill of Rights did not come soon enough to help them. Additionally, the returnees had to confront the turmoil of the Economic Recession (1918) and Economic Depression (1929), as well as the realities of contract labor employment. Some would die, while others would find themselves in prisons, both for farm labor union activism.

"Today, we find the WW1 Pilipino veterans buried in the Arlington, the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, the Presidio and other military or civilian burial grounds, unnoticed and unsung. Others were buried with their ships that were sunk by the enemies during the wars, unrecovered and unhonored.

"Today, their numerous descendants reside in every corner of the world. Rooted in deep family military traditions, many of these descendants had served during times of peace, as well as during WW11, Korea, Vietnam and Iraq wars.

"Undeniably, whether they served in the European military trenches or in the U.S. military support services, these valiant WW1 Pilipino soldiers had served the cause of peace and liberty to benefit all of us. They also swear allegiance to serve the flag of the United States during the time it was a seditious act for Filipinos to display the Filipino flag in their native land under the rule of the colonial U.S. government (Sedition Act of 8/23/1907 in addition to the Sedition Law of 11/14/1901 that imposes death penalty or long imprisonment for Philippine independence advocacy).

"Therefore, to us remain the sacred task of engraving their names and military legacies in our hearts. Let their memories inspire us, that we may work together to reclaim the rightful place of our Pilipino soldiers in the military history of the Philippines, the United States and the world. This awareness of our unique history is the responsibility of every living Pilipino ..."

Sources:

1. Kalaw, Maximo M. (1919). Chapter IV. Filipino Loyalty During the War. Self-Government in the Philippines. New York: The Century Company. 59-75. Retrieved from http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ahz9412.0001.001

2. Reyes, I.Q. (1925, July). They Served Uncle Sam in His Foreign Wars. The Philippine Republic. 2(7):19. Retrieved from http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acc6198.1924.001

2. Reyes, I.Q. (1925, July). They Served Uncle Sam in His Foreign Wars. The Philippine Republic. 2(7):19. Retrieved from http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acc6198.1924.001

3. VFW PA Post 1063. (1928, Jan-Feb). Boosters for Filipino Veterans. The Philippine Republic. 5(1):2. Retrieved from http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acc6198.1928.001

5. VFW PA Post Directory at http://www.vfwwebcom.org/pa/postdirectory/1/.

7. Filipinos WW1 US Military Service Homepage at http://filipinos-ww1usmilitaryservice.tripod.com/index.html

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Have you seen any mural by Enrique Liborio Ruiz?

|

| Charcoal study for "Mindamora" (1928) |

He was a senior high school student at Far Eastern College when Enrique Liborio Ruiz took nighttime courses under Fernando Amorsolo, I.L. Miranda and Vicente Rivera at the University of the Philippines School of Fine Arts. Upon graduation, he and his parents went to the United States and enrolled at Yale University where he got his bachelor’s degree in fine arts.

|

| "In Doubt" (June 1930) |

In Yale, his interests got diverted to architecture and mural paintings, visiting public buildings in America noted for their mural decorations, and during vacations, working with acclaimed muralists Eugene Savage and Ezra Winter and stained glass window maker Emil Zundel. Galo B. Ocampo (1939) would later note the influence of Savage and Winter in the mural paintings he was doing in the Philippines.

|

| June 1930 Panel |

|

| July 1930 Panel |

In 1927, he met Juan Arellano, supervising architect of the Bureau of Public Works at that time, who was visiting New York. Arellano encouraged him to study Javanese art, telling Ruiz that this is best suited for the Philippines.

Ruiz was back in the country in January 1930 after his graduation and a tour of the art scene in Europe. He got employed with the Bureau under Arellano, already the Chief Consulting Architect of the Government, to prepare mural decorations for public buildings. Even at that time, funding for such endeavors was hard to come by, and there’s no knowing if the Ruiz plans ever got to be painted, and if so, did they survive the bombing of Manila or the scourge of time?

|

| January 1931 Panel |

In June 1930, he did the front page cover “In Doubt” of Philippine Magazine, which editor A.V.H. Hartendorp said was the portrait of a Filipino lady that Ruiz met in the US while he was in Yale. The artist would do a series of twelve decorative Filipiniana panels for the magazine from June 1930 to May 1931 (5 of them shown here). [Who could be keeping them?]

Ruiz did not stay long with the Bureau. In 1932, he was already running his own business company devoted to decorative work and murals, and an early work was at the University Theater on Taft Avenue.

|

| February 1931 Panel |

This company could be this "group of artists [that] included Vicente Manansala, Victor Loyola, Marcelino Sanchez, Arsenio Capili, Lu Ocampo and Recarte Puruganan doing mural paintings with muralist Architect Enrique Ruiz as contractor and designer,” which Martino Abellana, known as the dean of Cebuano painters, joined early in his career. The group was able to finish two big murals before the outbreak of World War II -- a religious mural at the San Marcelino Church and the mural of the Time Theatre. This group or Ruiz himself could have done the mural in the Manila Hotel and in a room in Malacanang. [Are these works still around?]

In his column City Sense in the Philippine Star (2008, December 27), Paulo Alcazaren wrote about the “magnificent mural” at the Time Theater comprising three panels: ‘The right panel features the “Vision of the Architect,” …the central panel tells the story of “The Wooing of Maria Makiling” … [and] the left panel portrayed “The influence of film,” showing the “producer upholding the contribution” of his art, the scripts, cameramen, actors and a “family”of artists towards the production of the movies shown in the theater.’

In his column City Sense in the Philippine Star (2008, December 27), Paulo Alcazaren wrote about the “magnificent mural” at the Time Theater comprising three panels: ‘The right panel features the “Vision of the Architect,” …the central panel tells the story of “The Wooing of Maria Makiling” … [and] the left panel portrayed “The influence of film,” showing the “producer upholding the contribution” of his art, the scripts, cameramen, actors and a “family”of artists towards the production of the movies shown in the theater.’

|

| April 1931 Panel |

Hartendorp (1930) listed some works that Ruiz did in the United States. They should still be around:

1. “Mindamora” (1928, New Haven), “a painting showing the legendary queen of Mindanao receiving tribute from Sulu. A Korean friend posed for one of the male figures, but the magnificent queen was drawn without a model and entirely from his imagination.”

2. “Radha Darshan” or “Call of Love” (1929) drawn from Hindu mythology, which was exhibited in the Grand Central Galleries in New York, and which won the second Prix de Rome, offered to American art students by the American Academy in Rome.

3. “Saras Vati” (1928), “a small jewel-like painting of the Hindu goddess of culture.”

4. A commissioned work foe a Connecticut millionaire, “an allegorical painting, representing modern New England, for his private library”

5. “The Holy Family”, stained glass window of the Holy Ghost Church, Edgewater, New Jersey (executed before he returned to the Philippines)

5. “The Holy Family”, stained glass window of the Holy Ghost Church, Edgewater, New Jersey (executed before he returned to the Philippines)

Sources:

1. Hartendorp, A.V.H. (1930, June). Enrique Liborio Ruiz, Painter. Philippine Magazine. 27(1):14-16. Retrieved from The United States and its Territories, 1870-1925: The Age of Imperialism at http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acd5869.0027.001.

2. "Four O'clock in the Editor's Office." (1932, February). Philippine Magazine. 28(9):488. Retrieved from The United States and its Territories, 1870-1925: The Age of Imperialism at http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acd5869.0028.001.

3. Ocampo, Galo B. (1939, October). Mural Painting in the Philippines. Philippine Magazine. 37(10):408-409,421. Retrieved from The United States and its Territories, 1870-1925: The Age of Imperialism at http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ACD5869.0036.010.

1. Hartendorp, A.V.H. (1930, June). Enrique Liborio Ruiz, Painter. Philippine Magazine. 27(1):14-16. Retrieved from The United States and its Territories, 1870-1925: The Age of Imperialism at http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acd5869.0027.001.

2. "Four O'clock in the Editor's Office." (1932, February). Philippine Magazine. 28(9):488. Retrieved from The United States and its Territories, 1870-1925: The Age of Imperialism at http://name.umdl.umich.edu/acd5869.0028.001.

3. Ocampo, Galo B. (1939, October). Mural Painting in the Philippines. Philippine Magazine. 37(10):408-409,421. Retrieved from The United States and its Territories, 1870-1925: The Age of Imperialism at http://name.umdl.umich.edu/ACD5869.0036.010.

4. “Martino Abellana, Dean of Cebuano Painters”. Cebu Artists Inc. Retrieved from http://cebu-online.com/cai/abellana/abellana.php

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)